Diversifying Medical Training: A Step In The Right Direction

Credit: Shane Scott

By Amani Bayo

What does it take to stimulate change? Arguably, all great history-makers possess the ability to invoke change. Despite facing mountains of obstacles and pressure from an immigrant family, an Ohio State medical student has shown he has what it takes to lead the stampede of reforming racial disparities in medicine.

From the small parish of St. Mary, Jamaica, fourth-year medical student, Shane Scott, said he initially had zero intentions of entering the medical field. Now, he is the Md/PhD candidate that has pioneered the manufacturing of manikins of different skin colors.

Scott said when deciding which medical school to attend, he participated in demonstrations that included medical equipment for potential students to practice on. Although high-spirited, Scott said he noticed a substantial lack of diversity in the skin color of the manikins.

“I thought maybe it was one school and it was limited so I let a few pass but then institution after institution after institution it was kind of sort of the same thing,” Scott said. “I was like this is cool but none of them look like my grandma, none of them looked like my mom, my family members, uncle, aunts or even my colleagues that were some of the reasons why I wanted to go into medicine to begin with.”

Scott said the College of Medicine’s welcoming atmosphere had encouraged him to do the research and present a palpable argument about the disparities in medical equipment to members of the Clinical Skills Education and Assessment Center, such as associate director James Read.

“My vision was that for every single simulation that is carried out by OSU or across the country, I want it to have Black and brown patients represented,” Scott said.

Scott said he recognized an issue that had long been overlooked by medical practitioners before him and many were stunned by the seemingly obvious disparity in medicine. Scott said after the trivial process of applying to medical school, it's understandable for students who are accepted to solely focus on making it through.

“We’re so indoctrinated into whiteness being predominant in a lot of spaces,” Scott said. “When you enter such spaces it's easy to be jaded and it's not that they don't value representation it's just that feeling of ‘let's put our head down and keep going.’”

Scott initially had his aspirations set on becoming a translator for the United Nations, yet the whispers of his grandmother’s prophecy of being a doctor and an unforgettable chemistry course at Brandeis University had led him on a path of medicine.

Scott said his relatively last-minute venture into medical school had left him ill-informed of the grueling process of applying to medical schools, like taking the MCAT, which led to Scott being rejected twice before realizing he may need to garner more skills.

“If I get rejected I need to know why,” Scott said. “I ended up applying to attend the medical sciences graduate program at BU, got in there, and spent a year proving to myself that I belong.”

Scott said throughout his journey the looming awareness of the lack of Black male representation in medicine had influenced him to personally commit to encouraging incoming students of color to continue pursuing this field.

“I committed, I was going to tutor every single Black kid that came after me to make sure they stay in Chemistry,” Scott said. “Some of them are doctors already.”

As if the time Scott took to become a worthy candidate for medical school had finally paid off, Scott said he had been accepted by numerous colleges on his third attempt, however, was now carrying a new burden of family pressure to make the best decision and make his parents proud.

“Because of the emotional state that I was in at the time I knew I needed to get as much information to make a decision that didn't just do away with what my parents wanted or needed,” Scott said.

Scott said he chose the College of Medicine because of how welcomed he felt and the fact that there were five other Black men also alongside him. In a mixture of relief at finally achieving this goal and a sense of belonging, Scott said he felt empowered to ask advisors about the lack of diverse manikins.

“I felt welcome here and felt encouraged to ask that question here and the response I got wasn't pervasive and rude, it was honest, ‘I don’t know,’” Scott said. “I wasn't necessarily upset about it or as enraged, I just felt like this was the next step to get to where I needed to be.”

Scott said it was then that he leaped into action with the help of friends and mentors to conduct research and present a factual case to the head of the College of Medicine to change this discrepancy. Part of this research process was addressing myths that supported only using light-toned manikins to better locate veins.

“When I spoke to people who I knew in the medical field like phenopuncturaists were like no, that's not the right technique, you don't see veins, you feel for them,” Scott said.

To raise awareness Scott said he ran for class president in November under the platform #manikins4allskins to gain support from his peers and raise awareness. Scott said in the campaign he pointed out the historical non-consensual contributions Black and brown bodies have made to medical simulations and the injustices surrounding Black exploitation that led to the erasure of representation that taught diverse students that they did not belong.

“I feel like I walked in the space way more empowered than I would have otherwise been if I was accepted on the first try,” Scott said. “One of the things that I promised myself that I would do was explore my role as a leader.”

Read said now, in support of the College of Medicine DEI initiative, the CSEAC has committed to seeking out manufacturing companies that can produce diverse medical equipment to better represent the patient population.

“What's happening now, and we're a part of this, is that some of the larger players within simulation have started to say that that's unacceptable and we need to have more diverse options. That includes skin tone, it includes having more female presenting ones,” Read said.

Read said because of the culture of America, white males are often considered the standard, default model for human representation which has led manufacturers to only produce a single type of manikin.

“Overall, the manufacturers, I think, did that because it was much easier to manufacture a single line of devices so they just decided based on our cultural perspective and everything else that they were all going to be white male as a starting point,” Read said.

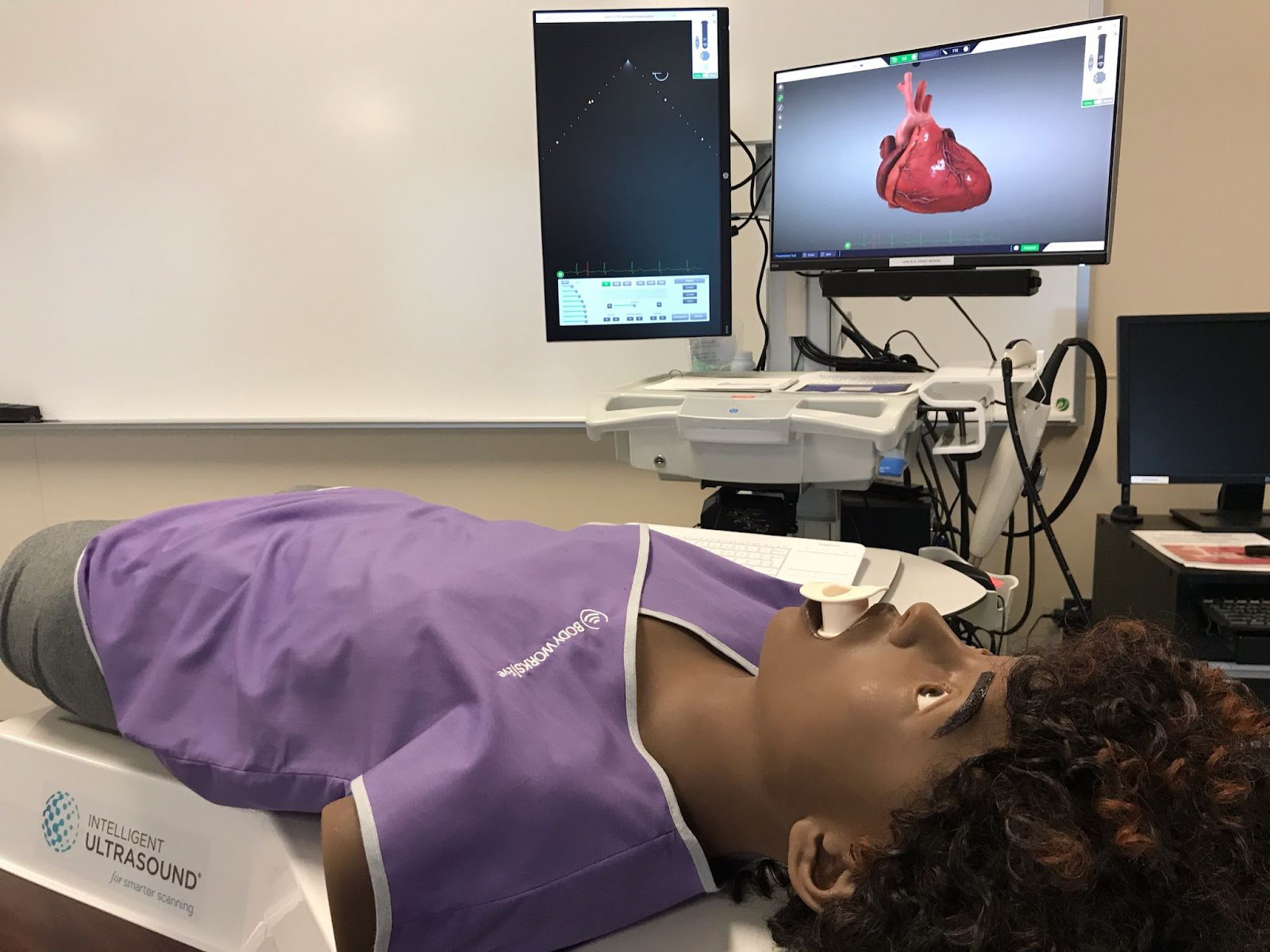

Manikin of color in a research lab.

Credit: Shane Scott

Additionally, several other students have tagged onto Scott’s initiatives by including suture pads of color and establishing organizations to further the implementation of inclusivity in medicine, Scott said.

Scott said he received an overwhelming amount of support for his advocacy. However, he said he still faced the stigma of being a social advocate and a practicing physician.

“I think that in medicine leadership isn't taught. I believe that most people who gain leadership positions in medicine they've been around a long time, someone said ‘Oh let me reward you with this position,’” Scott said. “I want to be a physician who is also a social advocate; we are just the center of a lot of people’s lives when you think about health.”